By: Sandy Abdelmessih

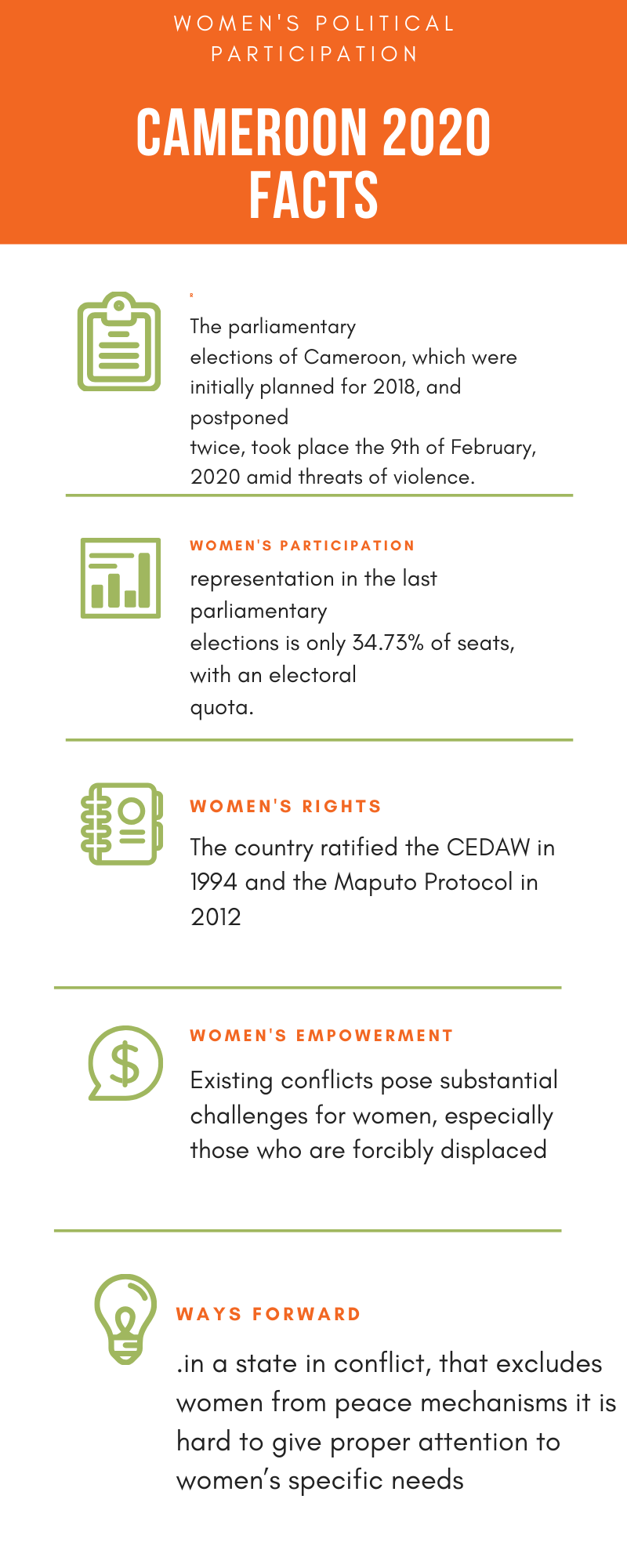

The parliamentary elections of Cameroon, which were initially planned for 2018, and postponed twice, took place the 9th of February 2020 amid threats of violence. The parliamentary term is five years, with the last round held in 2013. The announcement of the date of the elections triggered remarkable violence in the country.

Since the announcement of the Parliament and Municipal twin elections in November 2019, the armed conflict between separatists and the army has unprecedentedly escalated. On the one hand, separatists want full independence of the Anglophone Northwest and Southwest from the Francophone State of Cameroon. On the other hand, the ruling government has proposed unsatisfactory intermediates which were refused by the separatists and resulted in armed conflict that killed over 3000 people over the last three years.

Since December 2019, armed separatists, who oppose the decision to have the elections in February, have committed many crimes that range from killings, abduction, extortion, threatening anyone who wants to vote or take part in the elections. They threatened elected members to stop them from holding political positions, and consequently scared people who wanted to vote. In fact, some of the candidates have resigned their positions to protect themselves. Simultaneously, the army has burned houses, arrested, and killed people in the anglophone regions.

People living in Anglophone Cameroon face violence both from the army as well as armed separatists. Although the authorities ignore the impact of the conflict between the army and armed groups, it has affected the lives of people living in the anglophone region since 2016. As of December 2019, 679000 people have been forcibly displaced, according to Amnesty International, whilst 52000 have fled as refugees to neighboring Nigeria.

Since October 2016, the conflict between Yaoundé and armed separatists have never stopped. Instead, it is getting more violent, with an amplifying impact on the lives of 20% of the population who live in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions. Meanwhile, 10% of the population in the far North are under attack from Boko Haram Jihadists.

Women’s political participation

Women won the right to vote and stand for election in 1946. They make up to 50% of the population. However, their representation in the last parliamentary elections is only 34.73% of seats, with an electoral quota. Women’s representation in government, senate and municipal councils is even lower. Additionally, there have been no females selected for presidential elections 2018, although 45% of registered voters are females.

Cameroon ranks 96th out of 153 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index. The country ratified the CEDAW in 1994 and the Maputo Protocol in 2012, and established the ministry of women’s empowerment and the family. However, cultural and social norms cripple women’s political participation. For potential voters, their male family members guide their choices and for potential candidates, male family members could refuse to let them run, because they are afraid that might affect the quality of their labor inside the house.

77.22% of seats were won by the Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (RDPC/CPDM). In a single-party domination structure, it is even harder to practice opposition, or boycott elections to protest the status quo. Authorities use arrest, torture, and murder to silence opposition and to punish armed groups’ supporters. Women are affected in different ways. Some have been subjected to torture when detained by the State Secretariat for Defense, while others have family members and children being abducted, killed, detained and/or tortured. Moreover, conflict poses substantial challenges for women, especially those who are forcibly displaced. They have to generate income to help their husbands who can no longer find jobs, while enduring increased domestic violence. However, the government has encouraged people, and especially women to participate in the voting. Also, an overall fear of possible violence has disabled a safe and free atmosphere for women to rally, lobby, or even vote, after the clear threats of armed separatists.

Conclusion

Cameroon is lagging behind in terms of women’s political participation. The ongoing conflict makes it even harder to establish sustainable development and stability. Additionally, in a state in conflict, that excludes women from peace mechanisms and perceives them as only victims, it is hard to give proper attention to women’s specific needs. A lot has to be done to narrow the political gender parity gap.