I grew up surrounded by bicycles. My father owned one. I used to watch him fix a puncture, placing a patch where a sharp stone had penetrated the tyre. His bicycle was black, steady and heavy. In the villages a bicycle was a sort of emergency vehicle, even used to carry the sick to hospital.

When I moved to Harare, again I saw men cycling to work, often to places where public transport was scarce, such as the industrial districts and the low-density suburbs, where the white and black middle classes live. They worked as guards for businesses and homes, cooks and gardeners. While there were no official cycling tracks in Harare, in some parts of the city the pedestrian paths were wide enough to ride on.

In general, transport was a daily nightmare. Buses, public and private (licensed estate cars or minibuses known locally as emergency taxis), were always piled to over capacity with passengers.

People stood at roadsides waiting for any form of transport to take them to work. Emergency taxis, the estate cars, piled people in through the boot, a process that involved entering head first, keeping the head low, then sitting sideways with your legs straight together, as if in preparation for a yoga posture. The next passenger to get in sat opposite, and so on.

The economically advantaged white Zimbabweans rarely suffered from the same kind of indignity as black people when it came to public transport. Sometimes private motorists stopped to offer people a ride for payment. For an attractive woman, it was easy to get transport. Men stopped for you. Then I saw a woman cycling, and that set off a bell in my mind.

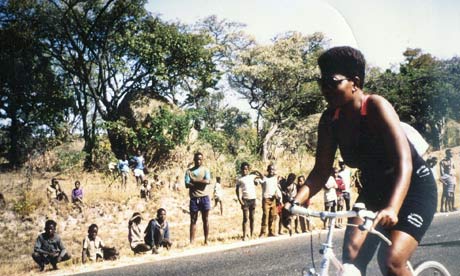

She was Katrina, a Swedish woman whose husband worked at the University of Zimbabwe. When Katrina and her husband left Zimbabwe, she left me her beautiful white bicycle as a gift. I was so excited that I cycled to work, even though I was in what one might call a learning stage. During the first weeks I kept off the main roads, fortunate that the pedestrian sidewalk was wide enough to ride most of the way.

People stared at me. I heard them telling each other in Shona that I was probably an American. Cars slowed down. Windows were rolled down, male heads would emerge and ask why I was cycling. A woman like me shouldn't be riding a bike, the men said, and wanted to know where I lived so they could pick me up. I would pedal away. An old classmate saw me and laughed hysterically. Sometimes I felt like a foreigner.

I was no longer a hostage to religion, tradition or men. I was free. On my bicycle I felt like I was in a room of my own.

I thought about what most women who relied on public transport, or on lifts from passing cars, were subjected to. I remembered with disgust how I often I had to fend off advances from men who stopped to give me a ride. I sat tight on my seat while being interrogated about my personal life: was I married? No. Then a smile, followed by "do you live alone?" Yes, then a wider smile. "Can I come and pick you up after work?" and so on. Sometimes a hand moved from the steering wheel and found its way to my thigh. A few times I yelled at the driver to let me off. Other times I pretended that I had reached my destination.

When a car would stop for me, first I'd peer in and examine the man's face. Sometimes I refused to get in. I became an expert at making snap judgments. Some men took detours to prolong time with me – their prey – for the purpose of completing the seduction. For some women these rides ended in rape. Fortunately, that never happened to me. But no woman was safe on Zimbabwe's roads.

In some parts of the world, a car is often the weapon of choice in the oppression and entrapment of women.

When I arrived in New York 10 years ago the first thing I looked for was bike lanes. But I was disappointed – to me, it seemed just like Harare. I saw a couple of bike lanes in Manhattan, one along the Hudson River. Since then, the city's Department of Transportation has made a lot more effort to make people like me, cyclists, more and more welcome.

• After leaving Zimbabwe, Jane Madembo studied mass media and communication at Fordham University. She now lives in Harlem, New York. Her work has appeared in the Zimbabwe Times and South Africa's Mail and Guardian.

from the daily ordeal of Harare's public transport system. Photograph: Jane Madembo