Women, Peace & Security

Uganda received its one millionth refugee from South Sudan on 17 August. This influx of people, many of whom have fled terrible violence to seek sanctuary in northern Uganda, has put a significant financial strain on the country and in particular its northern region.

The Ugandan government has looked to external actors for assistance. It hosted a conference in August where international donors pledged support to the tune of $352 million: a significant sum, but still a long way short of the $2 billion that Kampala and the United Nations had hoped to raise.

Stephen Oola, founder of the Amani Institute Uganda, a Gulu-based think tank, is adamant that “historically refugees have been used by the current regime for dirty political manoeuvres” and that the current situation is “no different”.

In this instance, hosting refugees gives the government leverage to resist international pressure on domestic issues such as the disputed 2016 elections and the campaign to amend constitutional age limits.

But with so much of the focus on the plight of refugees – who are undoubtedly in need of food, shelter, and basic support services – citizens of northern Uganda are once again being sidelined and ignored by their government: an approach that has characterised three decades of political dominance by the ruling National Resistance Movement.

President Yoweri Museveni’s time in power has been marked by a widening disparity between residents of northern and, to a lesser extent, eastern Uganda and those that live in central and western parts of the country; areas from which Museveni draws the bulk of his political support.

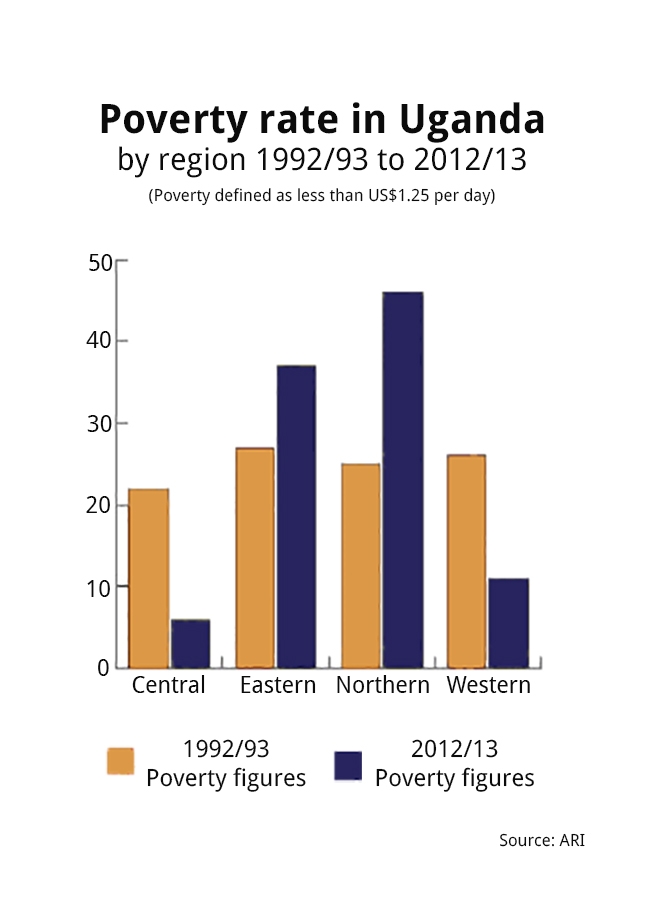

While significant strides have been made in reducing those living in poverty – between 1993 and 2013 the percentage of Ugandans living below the poverty lined dropped from almost 60 percent to 19 percent – in that same period the distribution has changed significantly.

From a fairly equal spread across the four main regions in the early 1990s, in 2013 almost half of those in poverty lived in the north, with west and central areas comprising less than 20 percent of the total. Rising levels of individual inequality are being replicated between regions.

Unquestionably the development of the northern region was stymied by conflict. Fighting between Ugandan forces and Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army spanned almost two decades (1987-2006). At its peak more than one million Ugandans were displaced in what was described as the “most neglected crisis in the world”.

But the conflict itself, and its aftermath, produced tensions and divisions between citizens in the north and the government, whose forces were accused of carrying out abuses against civilianswhen they were supposed to be protecting them. These accusations have not been investigated by the International Criminal Court (which has focused instead on the LRA) or national courts.

In the decade since the end of the conflict, efforts to rebuild infrastructure, improve basic services, and to encourage reconciliation have been outlined in a series of Peace, Recovery and Development Plans.

Now into its third iteration, progress made on improving physical infrastructure is visible but question marks remain over the government’s ability to deliver the “soft” components: schools and hospitals often lack the staff and equipment to function effectively and the “peacebuilding” element has been underfunded and gradually pushed aside.