Gender Issues Showlist

Women, Peace & Security

UNSCR 1325 calls on all parties to: protect and respect the rights of women and girls in conflict & post-conflict; increase women participation in all conflict resolution, peacekeeping and peace-building & to end impunity by prosecuting perpetrators of sexual and other violence on women and girls

index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=56&Itemid=1913

Human Rights of Women

Thirty six years after the adoption of CEDAW, many women and girls still do not have equal opportunities to realize rights recognized by law. Women are denied the right to own property or inherit land. They face social exclusion, “honor killings”, FGM, trafficking, restricted mobility, early marriage,...

index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=44&Itemid=1908

Violence Against Women

Violence against women is the most shameful human rights violation. Gender based violence not only violates human rights, but also hampers productivity, reduces human capital and undermines economic growth. It is estimated that up to 70 per cent of women experience violence in their lifetime

index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=69&Itemid=1912

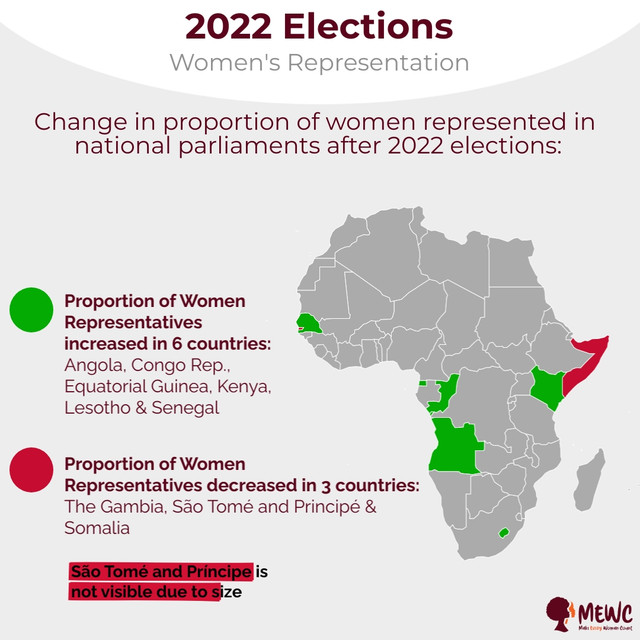

Political Participation & Leadership

Where women are fully represented, societies are more peaceful and stable. Women political participation is fundamental for gender equality and their representation in positions of leadership must be a priority for all Africans governments.

index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=65&Itemid=1911

Latest News

- COTE D'IVOIRE: South-South Meeting to Promote Gender Equality and Combat Deforestation

- RWANDA: Rwanda Set to Launch Cervical Cancer Elimination Plan

- NIGERIA: Over 5,000 Nigerian Women Stranded in Iraq - Govt

- SUDAN: Healthcare Collapse Threatens Pregnant Women in Sudan's Sharg El Nil

- GHANA: President Nominates 12 More Ministers

- Senegal: Parliamentary election 2024

- Mauritius: Parliamentary election 2024

- Ghana: Presidential and Parliamentary Elections

- Botswana: Parliamentary elections 2024

- Algeria: Presidential Election 2024

MALAWI: We Found A Way To Reduce Gender Bias In Malawi’s Nutrition Policy

Source: The Conversation UK.

Policymakers often struggle to disentangle themselves from their upbringing, not least when they think about gender. For example, many policies emphasise the role of women in nutrition policies – those intended to ensure peoples’ good health through informed access to safe, healthy and adequate food – because in many societies cooking is considered to be a woman’s responsibility. By focusing on women, these policies are thought to be gender-responsive. But that’s often not the case.

In 2016, Malawi set about renewing its nutrition policy, which had been in place since 2007. We conducted a policy dialogue to assess whether the new draft policy incorporated gender appropriately.

Participants in the dialogue included officials from the departments of nutrition and gender, civil society organisations, NGOs, donors and community members. We offered them a methodology we’d developed to reveal policymakers’ gender bias.

Using this analytical tool, we found that the existing policy reinforced the stereotypes of women’s roles, such as providing childcare. The policy acknowledged that men had a shared responsibility for housework and looking after children. But it suggested that men’s involvement was important only to give women more time to care for children.

A new policy was drawn up and accepted in 2018. We then conducted a case study of Malawi. This pulled together the findings of research that had informed the policy making process, and showed how the policy was improved. It also offered insights into why nutrition policy doesn’t always take proper account of gender.

By identifying that Malawi’s initial nutrition policy overemphasised women’s roles in nutrition, which in turn perpetuated gender stereotypes, policymakers were better able to understand this bias. They could then develop gender-responsive policies which foster cooperation between men and women.

Background to the dialogue

The first observations we had into incorporating gender in policy in Malawi was a study that began in 2015 that focused on men’s involvement in maternal and child nutrition. It pointed out that traditional gender roles tended to get in the way of women and children accessing the nutrition they needed.

But the research also found that gender dynamics were changing in the country. Some men were helping to cook, clean and look after children. This gave women more time to earn income and pursue their own interests. This was a shift from older traditional roles.

The study suggested that policymakers should consider men’s role in nutrition.

We also conducted an analysis of whether these changes in gender roles were reflected in Malawi’s 2007-2012 National Nutrition Policy. We wanted to know if the policy was gender-responsive, gender-blind or gender-tepid.

This background work formed the basis of the methodology we used in the dialogue with policymakers in 2016.

We created an integrated framework for gender analysis in nutrition policy by combining two existing gender analysis tools. These were the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation gender mainstreaming in nutrition framework and the World Health Organisation gender assessment tool.

We used the framework to assess Malawi’s first nutrition policy, developed in 2007.

Dialogue

We found that Malawi’s first nutrition policy was silent on the role of men. It didn’t challenge the idea that women are the only ones responsible for nutrition. Even in focusing on women, the policy did not consider the constraints they face in accessing nutritious food. For example, women in rural Malawi typically do not control household income and expenditure. They often can’t make independent decisions about buying food and improving the household’s nutrition.

But there were opportunities to get around these barriers. For example, the 2015 study found that when men received information on nutrition during their partner’s pregnancy, they tried to ensure that their partners got the food they needed. Men took pride in making sure that their families were healthy.

Policymakers had not considered the changes in gender roles and responsibilities that were taking place in communities. They had missed an opportunity to use these changes to improve nutrition.

We concluded from our study that the policy was gender-blind. One of the reasons for this is that nutrition experts aren’t necessarily gender experts. Their upbringing also influences how they interpret gender.

Informing policy

Our dialogue helped policymakers analyse the draft nutrition policy and identify gaps. As a result, some changes were made to the final policy that was passed in 2018. It acknowledges that men should share responsibility in housework and childcare so that women have more time to pursue other activities.

This process also informed the development of Malawi’s nutrition strategy. The strategy highlights the important role traditional leaders play in influencing how men and women interact. It emphasises the role of traditional leaders in motivating men to participate in activities that have traditionally been performed by women.

Our methodology to reveal gender bias has since evolved into an animated series that guides policymakers, researchers and others through the process of conducting a gender analysis.

The journey from background research to dialogue and policymaking has been documented in our 2019 case study.

Our work in Malawi provides a template for other countries. It shows that nutrition policies offer opportunities for rethinking socially imposed gender roles. But the first step is to make policymakers aware of their assumptions.